13 February 2023

![]() 18 mins Read

18 mins Read

Blessed with natural good looks, high living standards and a proud multiculturalism, our major cities are no stranger to the top end of a ‘world’s best’ list. Aggregating data across categories stretching from stability and healthcare to culture and environment, annual rankings like The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Liveability Index – which counted five Australian capitals within its top 11 in 2021 – tell us in numbers what we know through lived experience. That on a sunny day on Sydney Harbour, its architectural icons sparkling, there are few places on Earth we’d rather be. That Adelaide during festival season has an atmosphere to rival anywhere. Or that slipping down a Melbourne laneway to sip cocktails in a hidden speakeasy is the stuff memories are made of.

Sydney’s other bridge, the Anzac Bridge, cast in golden light at sunset. (Image: DNSW)

But almost two years of lockdowns have taken their toll on our world-class capitals. What shape will they take as they begin to recover from this once-in-a-lifetime period of flux?

And with many of us taking this moment of collective pause to rethink how we live and work by quitting the city altogether, has decentralisation – in fact – become the key takeaway of the pandemic?

We have been sea-changing and tree-changing with vigour since the concepts entered the vernacular and enjoyed their first boom in the early 2000s: a zeitgeist inspired by equal parts economic upswing and SeaChange, one of the most popular TV programs in Australia during the late 1990s. But the wave we’re seeing now is inextricably linked to COVID-19. With many people presented with newly flexible working arrangements, seeking space and a more balanced lifestyle, we’ve been leaving the city in droves for a coastal or country idyll – ideally still within a stone’s throw of a metropolitan centre. For the first time in living memory, without overseas migration to backfill the loss, the populations of Sydney and Melbourne have gone backwards.

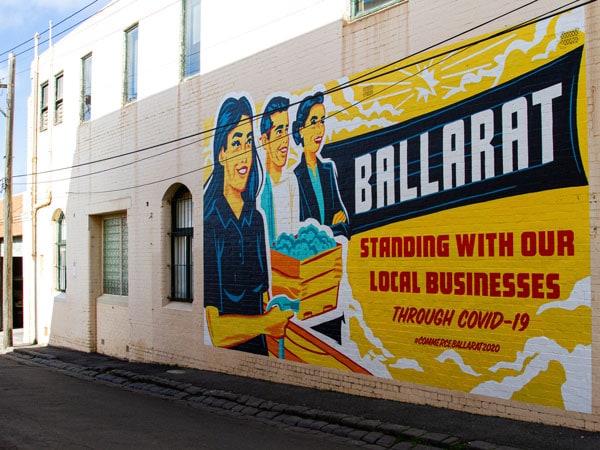

Out and about in Ballarat. (Image: Visit Victoria)

More than 32,000 residents left Melbourne in the 12 months leading to March 2021: a sharp shift that has impacted regional Victoria in something of an unprecedented way. The satellite cities of Geelong, Bendigo and Ballarat, radiating out from the state capital, are among the places whose growth has been accelerated by this so-called exodus. But these regional centres were already on a boom-time trajectory.

Ballarat’s Clothesline Cafe reflects the buzzing dining scene on offer in regional Victoria. (Image: Visit Victoria)

A study, Population growth, regional connectivity, and city planning—international lessons for Australian practice, published in August as part of a wider Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) inquiry, charts the current trend towards decentralisation. It cites how Ballarat has been identified by the Victorian government as a major centre for future growth, while Bendigo’s current population of more than 100,000 continues to grow at a rate higher than Australia as a whole and Geelong has enjoyed a sustained high-growth rate for decades.

Main Road Mural by Ballarat artist Travis Price taps into the city’s heritage. (Image: Visit Victoria)

They’re examples of regional centres really getting it right, says the study’s co-author Nicole Gurran, professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Sydney. Places that benefit from their proximity to a major metropolitan centre but are bolstered further by good infrastructure such as strong rail links. And crucially, says Gurran, they’re retaining their own unique identities, “while also creating really strong economic and cultural opportunities”.

She notes their regional tourism appeal, too: from excellent galleries increasingly mounting blockbuster exhibitions worth travelling for, dynamic dining scenes to rival those in the big cities, and creative ways to tap into local heritage, these characterful old towns built on fortunes wrought from wool and gold have reinvented themselves. “And what appeals to visitors is often wonderful when it comes to attracting and retaining local population.”

The sun rises over Ulladulla Harbour in the Shoalhaven. (Image: DNSW)

It’s no surprise, then, that our favourite holiday destinations are experiencing swells in population. The Northern Rivers region of NSW (including the Tweed and Byron Bay), with its constellation of breezy coastal towns and hinterland hideaways within two hours of Brisbane, has never appeared so attractive to those looking to leverage more lifestyle. Likewise an ever-increasing number of sun-seekers are dropping anchor in the Shoalhaven, a region of ocean-adjacent towns and villages on the NSW South Coast, ideally sandwiched between Sydney and Canberra. For Rachel Kent, moving here from the city was part of a much bigger picture that symbolises this shift.

Jim Wild’s Oysters in Greenwell Point. (Image: DNSW)

For 20 years, Kent shaped the curatorial vision of the Museum of Contemporary Art. In July she was announced as the new CEO of Bundanon Trust, the 1100-hectare Shoalhaven property gifted to the nation in 1993 by the late artist Arthur Boyd that is about to embark on the next chapter of its storied life. With a striking new $33 million museum embedded in the landscape, it will reopen in early 2022 with an expanded vision encompassing the tenets of art, environment and landscape that have always been at its core. Leaving a role in the heart of Sydney, and settling not far from where her cousins work as oyster farmers on Greenwell Point, was both a personal and professional choice for Kent informed by a profound change she was sensing.

New Bundanon Trust CEO Rachel Kent. (Image: Anna Kucera)

“People’s thinking around city and region has shifted quite a lot in recent years,” she explains. “And that shifting thinking has accelerated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. People are questioning where they position themselves in the world: how they engage, what is their community, and so on. For me, it seems a really logical step to reposition, and for an organisation like Bundanon to go through such a large transformation at this point – sitting outside of the larger city centres but the heart and soul of the region – is quite significant. It represents that change, I think, very well.”

Bundanon in the Shoalhaven is entering the next chapter of its life.

From the landmark new Shepparton Art Museum in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley to the Gold Coast’s $60.5 million HOTA Gallery and the state-of-the-art Ngununggula in the NSW Southern Highlands, major cultural centres emerging outside of our capitals are a weathervane of the country’s changing metageography. And each ambitious project reinforces a salient point. “I think it’s important to understand and acknowledge that communities are everywhere, not just in cities,” says Kent.

“Your regional centres are your powerhouses: where your produce and a lot of your infrastructure, business and industry comes from. It would be unwise to underestimate the power of the region, because in many ways that’s the heart of the state.”

Bundanon itself will become a centrepoint for the Shoalhaven, as well as for the wider state and country, and its social and economic impacts will reverberate strongly. It’s the right moment for the national cultural institution, says Kent. “It’s enmeshed with the ways that people are rethinking their relationship to place and to community. The Shoalhaven and South Coast region is uniquely positioned in that regard. Socially, culturally, economically: it’s really an area of growth.”

This fundamental shift is well overdue: Australia’s regions have long been earmarked as alternative population and economic centres to help ease congestion and housing affordability pressures in our capitals, as the AHURI study notes. But while this renewed interest in regional relocation creates a wealth of fresh opportunities, it can also pose challenges in terms of increased housing demand and rising prices.

Much-documented regional real estate bubbles are popping up everywhere from Port Fairy to Byron Bay, and rental vacancies are evaporating. For communities with smaller population bases such as the Northern Rivers and the Shoalhaven, it’s the speed of the change that creates challenges, says Professor Gurran. “When you get a really rapid population shift, even an extra 500 people could completely distort the housing market and result in a lot of pressure on services.” But, she affirms, such communities can be made ready. “Absolutely, it’s overdue to start looking at improving regional health and educational infrastructure, and regional transport.”

Byron Bay’s continued population growth is putting increasing strain on housing availability. (Image: Byron Bay Main Beach/DNSW)

There are both short- and long-term strategies that can be employed to help ease the pressure created by this sudden boost (which, with flexible work practices here to stay, looks set to be more than just a blip). Short-term policies include controls on the use of residential housing for holiday rental (particularly when it comes to those properties managed independently via online platforms that don’t have a local presence – the economic benefits of which, for the local area, are limited – as opposed to those professionally managed by locally based businesses). “So really thinking more carefully about where holiday homes might be versus making sure that there’s sufficient housing for the local workforce and local residents,” says Gurran. “That’s going to be a really important strategy.”

And in the longer term, “We need all levels of government to identify the need to invest in regional infrastructure,” she considers. “I detect some signs this may be starting to occur at the national level; Infrastructure Australia is recognising the opportunity associated with providing strong [transport, social and health etc.] infrastructure for regional areas … Some of this infrastructure is what high-tourism regions have been calling for, for a long time, because they’ve always experienced sudden influxes of people.”

Ultimately, population begets population.

“If you’ve got more people living in an area, then you’ve got more demand for schools and more demand for all of the other services, so that actually builds up a more diverse and sustainable population. And that’s what will make an impact on regional areas.”

While this change is significant, says Gurran, it won’t completely invert the economic geography of Australia, which for the foreseeable future will be concentrated in our capital cities. “You will always have high visitation as well as residents living, and wanting to live, in the major cities,” says Gurran. Sydney and Melbourne’s pruned populations are expected to bounce back as international studies and migration resume.

Tayla Broekman’s mural in Melbourne’s Bourke Place for Flash Forward. (Image: Nicole Reed)

And our city centres will always be our front doors: to our wider cities, states and territories, and to the country as a whole. But there’s recovery to be done first. In true Melbourne style, the cultural capital is turning to the arts to help reanimate its CBD. Flash Forward is one of a range of programs delivered by the City of Melbourne, designed not only to entice people back to the city – in the knowledge that investment in public art drives visitation – but also to support hard-hit hospitality, retail and entertainment industries in the process.

“With the support of the Victorian Government, we have employed more than 160 creative professionals at a time when so many have lost work,” says Lord Mayor of Melbourne Sally Capp.

This dynamic series of commissions connects a diverse range of contemporary visual artists and musicians by bringing their work together in 40 Melbourne laneways. It made perfect sense to combine the city’s world-renowned and locally loved laneways with artists and musicians – so integral to its reputation – at a time when public space is more important than ever, says Capp. The result is free outdoor galleries to be enjoyed into the future and live music for city residents and visitors alike in the new year.

A mural, Still, Life!, by Shawn Lu in Langs Lane is helping to reanimate inner-city Melbourne as part of the Flash Forward program. (Image: Nicole Reed)

Crucially, it’s a way to evolve past the pandemic while also acknowledging the profound impact it has had. “Flash Forward is a hopeful, engaging and uniquely Melbourne experience – responding to the widespread desire to ‘flash forward’ to a post-pandemic city while also acknowledging the challenges of the past two years,” says Capp. “[It] will become a legacy of artwork made during a difficult moment in time, so it was important to enable creatives to capture their responses to the pandemic honestly in their work.”

There’s another hopeful picture emerging, too. The blue-sky idea that the pandemic has the potential to fundamentally reshape our inner cities and the way we interact with them for the better.

“Health crises have always transformed cities,” says curator and Deputy Lord Mayor of Sydney Jess Scully, citing the big changes to the way urban centres were designed after the Spanish Flu in the early part of the 20th century as an example. “We’re going through a wave of that now. And what that means is that we’re going to reclaim space that we’ve been keeping in cities for traffic – to be places that you travel through – and instead make them into destinations. Reclaiming space from cars, for people.”

Deputy Lord Mayor of Sydney Jess Scully.

More than 260 businesses within the City of Sydney have been able to take over car spaces in front of their premises for outdoor dining and drinking and Scully sees this going further, with precinct-level closures that not only offer space to support businesses safely but will change the way we use the city going into summer. This will let us reclaim more space outside for hanging out and socialising, enjoying music, and generally being part of the entertainment. And it’s about time, Scully says: “Even though it seems like common sense, there have been a lot of barriers in the way. So I think that’s going to be a major change coming out of the pandemic.”

The pedestrianisation of George Street, the formerly traffic-logged arterial street of the Sydney CBD, has been in the works for over a decade. But now, the moment has met the opportunity says Scully, and the federal and state governments along with the City have collaborated on funding another stretch of its improvement. “We’ll actually have a ‘Rambla’: a place to savour and promenade through the heart of the city, which I think we all enjoy so much when we travel around the world. And now there’s nothing stopping us from having it here, too.”

This reclaiming of space to increase the focus on green and public space is at the core of the City’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2050’ long-term plan for a green, global and connected city, and this period may have brought this forward: whereas in the past it was ‘edge’ thinking, now it’s a no-brainer, says Scully.

“I think this has been a transformative moment in that it’s accelerated people’s expectations of the city.”

In a place like Sydney that is blessed with ample sunshine but an incongruous shortage of outdoor dining, this is a game-changer. “We’ve turned the bar into a full bar-patio, we’ve got tables everywhere outside,” says George Woodyard, owner of Bart Jr. in the inner-city suburb of Redfern. “It’s changed the whole vibe of the street – it feels amazing.”

George Woodyard, owner of Bart Jr. (Image: DNSW)

During lockdown, Woodyard ran the neighbourhood wine bar as a pop-up, Bart Mart, selling ready-to-eat meals, natural wine, takeaway cocktails, groceries and lobster rolls that quickly developed a cult following; this pop-up looks set to live on as a bottle shop across the road.

The Sydney wine bar ran as Bart Mart during lockdown and its lobster rolls became a cult hit. (Image: DNSW)

“Having an opportunity to test things out in a temporary way that we can learn from has been a huge advantage of this moment, too,” says Scully.

Another unexpected but exciting trend to have emerged, which feeds into the way we’ll use our CBDs in the future, is the recalibration of our city suburbs as a result of the five-kilometre rules and work-from-home regulations of lockdown. “What’s happening in Sydney is very similar to the sort of evolution of a city that you see in places like London, Paris or New York,” says Scully. “When you become a global city, you start to see other urban centres within that city develop and gain their own identity and gravity.”

Our home patches are no longer dormitory suburbs used simply for sleeping and playing at the weekend, but coming into themselves as centres in their own right where the opportunity for more bars, restaurants and cafes to have a steady trade during the week unlocks unlimited potential.

St Kilda in Melbourne is another thriving suburban village. (Image: Visit Victoria)

This has played out elsewhere, too. Balancing on the brink between working-class and gentrified, the Melbourne suburb of Moorabbin is where young professionals priced out of the hip inner-north might move to for a house with a garden and room to start a family. Its good infrastructure and bayside location have long had it tipped to become the Northcote of the south-east – something local hospitality operators Megan Kwee and Adam Cruickshank were tuned into when they opened casual fine diner Comma Food & Wine as Melbourne emerged from its lengthy second, but far from last, lockdown.

Comma Food & Wine executive chef Matthew Woodhouse with owners Megan Kwee and Adam Cruickshank. (Image: Sion Schluter/The Age)

And the cards they were dealt by COVID-19 played right into their vision of bringing an inner-city experience closer to home, proving a catalyst for the area’s upward trajectory. “Moorabbin has got a lot to offer and we feel like we have come in at the right time,” says Kwee, “because you’ve got a lot of people [living here] who know what they like in terms of food and wine, and now we’ve got this pull to the suburbs.”

Melbourne’s suburbs have thrived with spots like Comma Tuckshop embraced

by locals. (Image: Sion Schluter/The Age)

What started as a pop-up shop operating out of the eatery’s window over the subsequent snap lockdowns had evolved by the sixth lockdown into Comma Tuckshop: Allpress coffee and gourmet bagels served from a quirky roller-doored space in a former janitor’s store room. Its rough-and-ready opening and lower stakes aided by cheaper suburban rents and a supportive landlord gave Kwee and Cruickshank the freedom to take risks and evolve without the pressure to be perfect from day one. With executive chef Matthew Woodhouse onboard, they’ve innovated to create weekend specials like lobster bisque bagels that have been devoured with relish by local residents – who’ll be pleased to know the tuckshop is here to stay.

“If you have many more people working from home and eating and drinking close to home, that provides a sustainable base for those businesses to thrive,” says Scully. “So people can experiment, they can invest more, they can create more offerings in those alternative urban centres.”

And as our city suburbs continue to up the ante, our inner cities will need to keep pace.

“The offering in the downtown has got to be more interesting, sophisticated and appealing, because it’s now becoming an attractor for people who have great offerings close to home as well,” says Scully.

AHURI’s study on population growth, regional connectivity and city planning draws a similarly multilayered conclusion: that while concerns over economic recovery might lead to a favouring of CBD recovery, the international and Australian evidence reviewed suggests that economic and social benefits will be maximised by dual strategies that recognise the continued importance of agglomeration in our major cities, while also fostering regional areas in their own right.

Melbourne’s vibrant CBD has been hard hit by the pandemic. (Image: Visit Victoria)

So while the temptation when rebuilding our inner cities might be to focus on the future of commercial office space, co-author Gurran notes this strategy would be shortsighted. “Because Australian cities have actually [already] remade themselves over about a 30-year period into places for people to live and come to for recreational and cultural opportunities – and not simply places that you go to between nine and five, to go into an office tower.”

Our diverse inner cities can prove resilient to change, she says. “And so a strategy to reanimate our CBDs that continues to focus on the cultural, or the reasons to come to the city beyond simply going to work, will be – longer term – a much stronger basis for recovery. With the benefit of then also looking at regional centres and suburban villages.”

Thriving urban centres that are less business, more pleasure, paired with richly textured suburbs with local distinctiveness that add to the overall experience and eclecticism of a city. Booming regional centres with their own sustainable and diverse populations. These various outcomes shouldn’t come at the expense of one another but rather work together as elements of an ecosystem that makes all parts of Australia desirable places to live, work and play.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT