10 March 2023

![]() 5 mins Read

5 mins Read

We board the Tusa Dive T6, a 24-metre dive vessel, at the city marina, the other voyeurs and me. Soon we’re at sea and heading for Saxon Reef, on the Outer Barrier Reef 55 kilometres north-east of Cairns. It’s five nights after the November full moon, which shines across dark millpond waters at the reef mooring. The sea is a summery 27 degrees Celsius – perfect conditions for our oceanic orgy.

The Great Barrier Reef’s annual mass coral spawning has been called the biggest sexual event on the planet – and even the world’s biggest orgasm on the world’s biggest organism. Over two or three nights at various times between October and December, the waters of individual reefs across the 2300-kilometre Great Barrier Reef suddenly burst with new life – countless egg and sperm bundles released simultaneously by billions of coral polyps in a spectacular explosion of synchronous breeding.

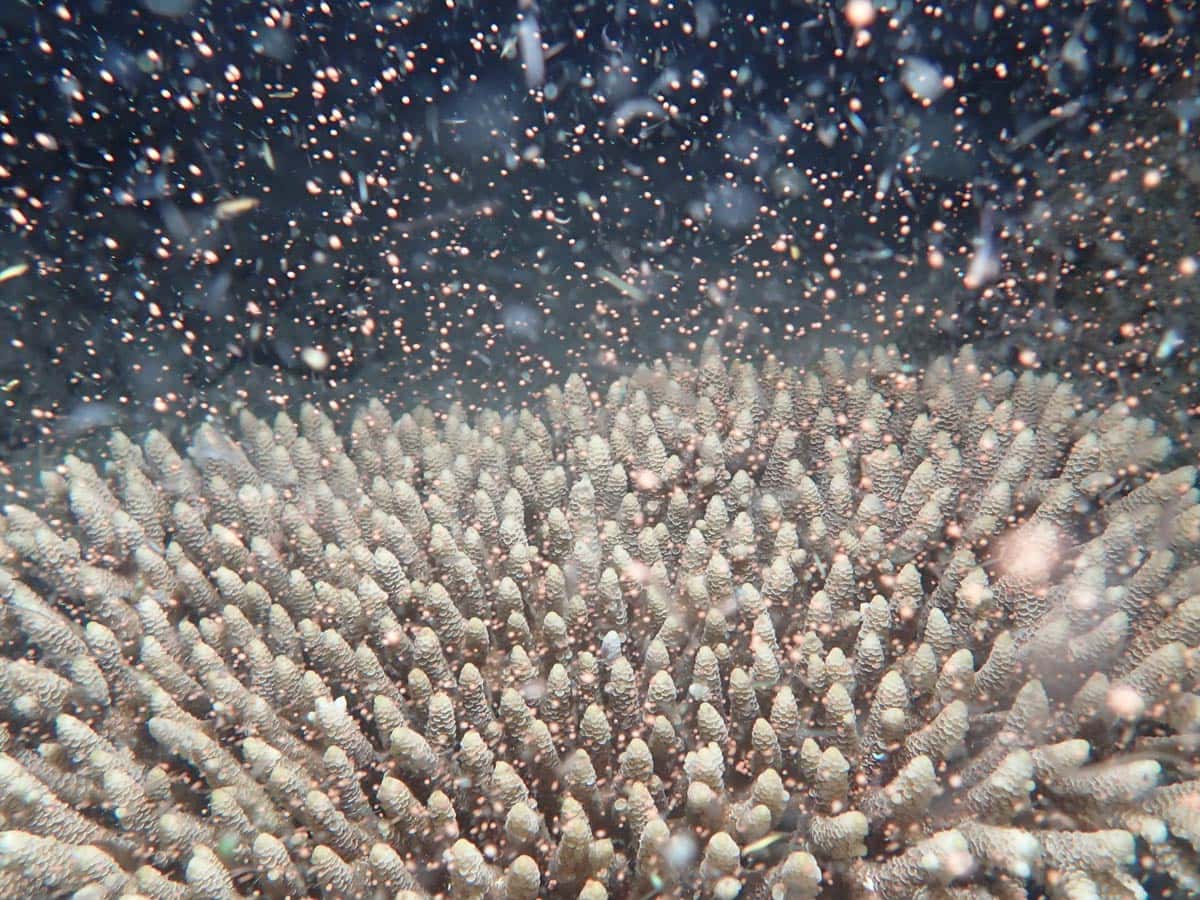

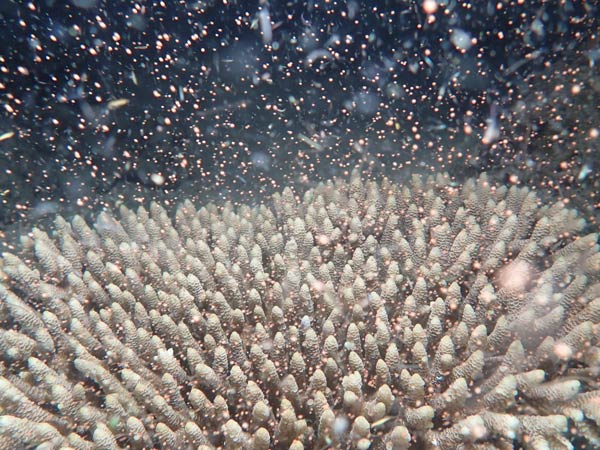

Close up shot of engorged arcropora ready to release. (Image: Gareth Phillips/Reef Teach)

Looking like a blizzard of tiny snowdrops, they bubble to the surface over a few nocturnal hours and form a pungent, pinkish slick. Splitting apart, the egg and sperm bundles fertilise en masse. The result: billions of pinprick-sized coral larvae, which a few days later settle back down on the reef to begin their life’s work of reef-building. Remarkably, this vast, vital aspect of coral life was unknown until 1981, when Australian scientists observed it on the Great Barrier Reef off Townsville.

Forty years later, with mass coral bleaching due to climate change and escalating existential threat, spawning seems a mighty and cheering demonstration of Reef resilience. It’s also emerging as a potential means of safeguarding the future: scientists now use the yearly boom to scoop up millions of healthy newborn corals for resettlement in bleach-depleted areas.

A control vessel monitors the waters during the coral spawning off the coast of Cairns.

A greater goal – to help coral fight deadly bleaching – also harnesses spawn power. Almost all corals keep algae in their tissue to supply vital nutrients. In overheated conditions they lose it and begin to starve – and bleach. During last year’s spawning, the Larval Restoration project mixed large volumes of coral larvae on a Cairns reef with more heat-tolerant algae, enhancing their ability to resist bleaching. Also, supplying algae so early in the life cycle (before it is naturally acquired) speeds growth, boosts health and improves survival chances.

Time to check out chapter one of that life cycle. Donning scuba gear – though plenty onboard choose to snorkel shallower parts instead – we descend into 10 metres of seawater, shadows and coral, lit only by the bright moon and our dive leader’s soft but wide-ranging torchlight. Visibility is excellent; there’s no chance of being lost in the night.

Duck diving on Moore Reef during its November 2019 coral spawning.

A spectacularly flame-patterned eel, thicker than an arm, slithers from its hole in a reef outcrop. A two-metre-long grey reef shark suddenly looms from the blackness and shoots along the sandy channel beside us, dwarfing two whitetip reef sharks alongside it. None pay us any attention; they’re on secret shark business. A trio of giant trevally are more interested, lurking just inside our beam, as if hoping we’ll light the way to prey.

For all these enchantments, the first dive ends with no spawning. We’re a tad early, it seems, but Mother Nature doesn’t publish timetables. Back on the boat, our surface interval passes with a welcome cooked dinner. And then, during the second (10pm) dive, it happens. A broad patch of coral, carpeted by white blobs, is brewing something marvellous. Suddenly we’re inside a snowdome. Rising above the coral are myriad snowy dots, shimmering as they flutter and fly before our eyes. Some seem to shine with an inner light. Against the inky backdrop of the night sea, they could almost be stars or meteors.

Flynn Reef erupts in an explosion of pink as corals release tiny balls containing sperm and eggs into the water. (Image: Gareth Phillips/Reef Teach)

You might think, ‘eeeww, swimming in sperm, no thanks’ – but it’s not like that at all. To hover weightless in the sea while meeting the first flakes of an underwater, upside-down snowstorm at night is a moment of pure wonder and magic. It feels like seeing Santa actually land his sleigh on the roof.

The extraordinary event gives the impression of being inside a snowdome. (Image: Gareth Phillips/Reef Teach)

But there’s also a grounding reality amid the sense of unreality, and that feels special too. It’s an intimate encounter with life’s grandeur, with that fundamental, never-say-die impulse to propagate that keeps the primordial cycle going. This is literal immersion in the miracle of life itself, this private moment between me and coral, silent but for my bubbling breath.

We’re not back in Cairns until almost 1am. The cabin lights are out and we’re dozing in the dark, the other voyeurs and me. Midnight has passed and it’s been such a magical night I wonder that the boat hasn’t turned back into a pumpkin. Cinderella went to the ball, and I’ve seen coral spawning.

Getting there

The Cairns marina is located within walking distance of most centrally located hotels.

Playing there

Spawning on Cairns’ reefs is usually within a week of the November full moon. Book here

Staying there

The design-focused Bailey in central Cairns is a great option.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT