16 February 2023

![]() 10 mins Read

10 mins Read

It’s a drizzly Wednesday night and the dining room of Emily Taylor is packed to the rafters with patrons chatting and laughing and dipping into share plates of super-spicy dumplings and massaman curry of beef and twice-cooked sticky pork. The hotspot Fremantle diner is tucked behind the equally cool Warders Hotel, which has revitalised a row of historic limestone cottages built in 1851 to house the warders of the nearby convict-built UNESCO World Heritage-listed Fremantle Prison.

Emily Taylor is the 450-person bar and restaurant nestled inside Fremantle’s beautiful Warders Hotel.

Both the restaurant and the hotel opened in late 2020, in the midst of the first year of the pandemic and seven months after Western Australia closed itself off from the outside world. “We’ll be turning Western Australia into an island within an island – our own country,” Premier Mark McGowan said at the time. It would be 697 days until it would open back up and rejoin the rest of the country.

But the women sitting next to me at dinner catching up on their week and the family a few tables away celebrating a birthday don’t look fatigued by the prolonged isolation. They look happy about snagging an in-demand table and glad to be feasting on great food, all at a boutique hotel that has been creating a buzz and pulling in crowds since its opening, without interstate visitors or international tourists.

Western Australia – and its capital of Perth – has always had an independent streak, an assured sense of its own value that has resulted in a confident self-reliance that is rooted in its remoteness, its rugged beauty and its singularity of landscape and attractions. It is fed by the fact that Perth has famously been labelled one of the most remote cities in the world (based on comparisons to cities of comparable size), and has endured a boom-and-bust history that has been ebbing and flowing since the gold rush and through the seemingly endless rise and fall of commodity prices ever since. It is these elements that might just have helped to insulate the city from the shock of an experience that laid many others low, bogged down in anxiety and self-pity, and resulted in it emerging from lockdowns and border closures with a new sense of hope for the future.

It seems to me that the embodiment of this collective positivity is the new WA Museum Boola Bardip (new to everyone outside of the state at least, having officially opened its doors back in November 2020), an award-winning, $400 million project that has revitalised the city, and re-engaged Western Australians in their collective history, stories and identity.

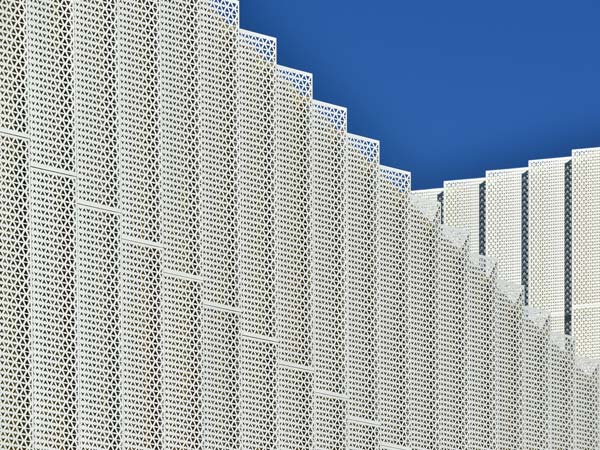

The sleek lines of the new building are shrouded in intricately patterned metal screens.(Image: Daryl Peroni)

Sitting on Whadjuk Noongar Country in Perth’s Cultural Centre, a large pedestrianised precinct that is also home to the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA), the State Library of Western Australia, the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) and the State Theatre Centre of WA, the structure is a triumphant melding of old and new, creating a space big enough – and ambitious enough – to fully represent the largest state in the country.

WA Museum Boola Bardip is a mix of heritage and contemporary architecture. (Image: Michael Haluwana, Aeroture)

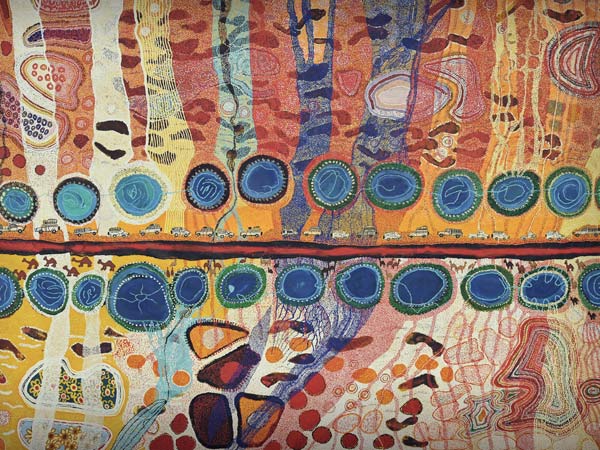

With a tagline of “Our people, our places and our role in the world”, the museum sets the bar high when it comes to inclusion. Boola Bardip means ‘many stories’ in the local Whadjuk Noongar language, and the use of it (which was decided on in consultation with the WA Museum Aboriginal Advisory Committee and the museum’s Whadjuk Content Working Group) seems to go beyond just naming the physical structure itself. If, as the official visitor guide states, the names we give places express their significance, history and identity, using the traditional language of the First Peoples who lived here speaks volumes about the focus of the museum on addressing the cultural disparities of the past through engagement and education, and integrating the histories and stories of the First Nations peoples of Western Australia into the collective history of the state.

The voices of First Nations people resonate throughout the museum. (Image: Tourism Westen Australia)

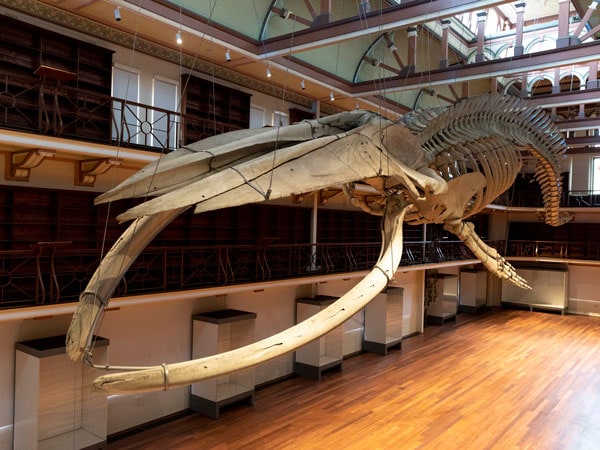

The building is impressive enough to be worthy of the task. Previously made up of a hotchpotch of buildings constructed in differing styles during different periods of Perth’s maturation, including the Old Perth Gaol (and its original well, which was rediscovered during the construction process for WA Museum Boola Bardip), completed in 1856, the Jubilee Building, which opened in 1899 housing the state’s art gallery, library and museum, The Beaufort Street Building and Hackett Hall, with its ornate Federation interiors of cast-iron spiral staircases, pressed-metal patterned roofs and skylights, the new structure, the joint project of design practices Hassell and OMA (fashioned as Hassell + OMA) sits beside, above and connected to these significant historic sites.

Dramatic golden spiral staircases announce intersecting pathways and encourage visitors to explore WA Museum Boola Bardip intuitively. (Image: Tourism Westen Australia)

“The original design brief was large and complex,” says Peter Dean, the principal in charge of the project, as well as being hugely aspirational. “It needed to be globally significant, internationally recognised, and emphasise the heritage of the site and buildings.” Taking inspiration from the vastness of the WA land, sea and sky, and the myriad stories of the people of Western Australia themselves, many elements in the design were informed and influenced by the objects found in the museum’s collection.

The melding of the new and old is seamless, with entire walls removed and installed with giant windows and viewing mezzanines that look from one building to the next; a giant cantilever shrouded in metallic screens hovers above Hackett Hall; and a gold seam, informed by the gold running through a giant piece of WA quartz, one of the first historical objects in the museum’s collection, forms a unifying central theme throughout, and a stunning focal point in the inclusion of a number of giant circular staircases also rendered in gold. The project also included taking responsibility for renovating and modernising the heritage buildings, from removing asbestos to installing insulation and making them all structurally sound. Every aspect has been done to exquisite effect, a fact not lost on the woman whom I overhear telling her family that it is the best museum she has ever been to – in the world.

The building is impressive enough to be worthy of the task. (Image: Tourism Westen Australia)

According to the museum’s CEO Alec Coles in his message in the Opening Guide, in developing the WA Museum Boola Bardip a commitment was made to focus on people first, and to share not tell the stories of the state and its inhabitants. Sharing is something Coles does enthusiastically when it comes to the museum he oversees; when I meet him within the soaring entrance hall for a run through of the space, he is instantly animated about the building and the collection it houses.

“I’m very pleased with the way it’s come out,” he says as we head into the museum, which boasts eight permanent exhibitions that concentrate on WA’s cultural and natural heritage, and feed into the museum’s three major themes: Being Western Australian, Discovering Western Australia and Exploring the World. “I’m delighted with the way they’ve incorporated the heritage buildings, but the thing I’m proudest of is the degree to which we engaged with the people of WA in creating it. We claim to have spoken to over 54,000 people in the creation of this, in terms of collecting stories, collecting ideas. We also had a principle that we wouldn’t speak for people who could speak for themselves, and that was particularly important with Aboriginal communities. You’ll find Aboriginal voices expressed throughout the whole museum.”

The exhibits spread throughout the museum delve into WA’s origins (land, water and sky), wildlife, people and treasures, as well as the stories of its First Nations peoples. It also provides a home for the skeleton of Otto the Blue Whale, which now hangs proudly above Hackett Hall and can be viewed from Hackett Gallery.

The iconic and much-loved skeleton of a blue whale takes pride of place at WA Museum Boola Bardip. (Image: Michael Haluwana, Aeroture)

“You can’t see it all in one visit,” says Coles of the size and scope of the museum. “If you were trying to go from the beginning to the end, you’d be exhausted and locked in for about five nights.” He encourages visitors to explore freely, starting on the ground floor at Ngalang Koort Boodja Wirn (Our heart, Country, spirit) in the Wesfarmers Gallery. “It provides a welcome onto Country for everybody, but particularly for our visitors who we’ve not yet been able to entertain or those from overseas who are maybe less familiar with Australian Aboriginal cultures.”

Coles leads me through the expansive space, from the Wildlife gallery, which he believes is most people’s favourite, and onto his own favourite, the Origins gallery. “When we designed [the museum], we always said, ‘We’re not going to build the old museum in a new building’, so we’re not going to have a bird gallery or a dinosaur gallery. All the galleries are kind of holistic; the world isn’t organised the way museums organise collections.”

As a result, exhibits are arranged in a way that allows visitors to dive in and out of different aspects of a collection without feeling like they are being forced through it on a set path or missing out if they don’t view it in one go. Coles explains there is no traditional bird gallery, but there are now more birds on display throughout the space than ever before. There are dinosaurs, but they are fleshed out and interactive rather than being just bones housed behind glass. The stories of some of the state’s residents detail their lives before they even arrived in WA.

An hour and a half later, Coles is still sharing stories of the gallery, but time has beaten us and I leave understanding the pull to return that the museum instils in visitors, and the reason this bold, shiny building is the perfect metaphor for the next stage in Perth’s story. “From the architecture and buildings, through to the galleries, collection, public and school programs and extensive digital content, WA Museum Boola Bardip is a place to enjoy, to learn, to debate and to imagine,” Coles says in the Opening Guide, which I read as I sit waiting for my plane back to the east coast. “It is about who we are, where we come from and what we can achieve together.”

The museum is a new landmark within the Perth Cultural Centre. (Image: Michael Haluwana, Aeroture)

The area where Boola Bardip stands has a history that stretches back thousands of years, when the ancient system of swamps, wetlands and lakes located there were a prolific hunting and foraging place for the local Whadjuk Noongar people. With abundant food sources, the area was also where people gathered to participate in cultural rituals and practices. A patch of the ancient wetlands has been replicated within the Cultural Centre, at the base of a stepped amphitheatre, with thriving native flora and fauna; the stepping stones and waddling ducks will be what captures the attention of kids.

LEAVE YOUR COMMENT